Scientists at the Swiss Light Source SLS have succeeded in mapping a piece of brain tissue in 3D at unprecedented resolution using X-rays – non-destructively. The breakthrough overcomes a long-standing technological barrier that had limited the use of X-rays for such studies. With the SLS upgrade now complete, the path lies open to imaging much larger samples of brain tissue at high resolution – and to gaining new understanding of its complex architecture. The study, a collaboration between Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and the Francis Crick Institute in the UK, is published in Nature Methods.

“The brain is one of the most complex biological systems in the world,” says Adrian Wanner, who leads the Structural Neurobiology research group at Paul Scherrer Institute PSI. How neurons are wired together is what his group are trying to unravel – a field known as connectomics.

He explains: “Take the liver: we know of about 40 cell types. We know how they are arranged. We know their functions. This is not true for the brain. And so, one could ask, what is the difference between the brain and the liver? If we look at a cell body in the brain and the liver, it’s not easy to distinguish the two. They both have a nucleus, an endoplasmic reticulum – they both have the same intercellular machinery, the same molecules, the same types of proteins. This is not the difference. What is really different is how the brain cells are organised and connected.”

Let’s talk numbers: in one cubic millimetre of brain tissue there are about 100 000 neurons, connected through about 700 million synapses and 4 kilometres of ‘cabling’.

How these neurons are connected to each other through synapses determines how the brain works. It is linked to diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Yet the complexity of this wiring in three dimensions is extraordinarily difficult to study. “If you take a neural network with 17 neurons, there are more ways to connect them than atoms in the universe, says Wanner. “So you can’t just try to model it. We need to measure it.”

It is on the backdrop of this immense problem that a major technological advance by Wanner and colleagues at the Swiss Light Source SLS – in collaboration with the Francis Crick Institute in the UK - stands.

X-rays peer into the ultrastructure

Currently, the go-to technique for this type of imaging is volume electron microscopy. As electrons penetrate only shallowly, cubic millimetres of brain tissues must be sliced into tens of thousands of ultra-thin sections. These are then imaged individually and computationally reconstructed to map the 3D connectivity of the neurons through the slices – a process that is very error prone and inevitably results in loss of information.

A solution lies with X-rays. These can penetrate millimetres – or even centimetres – and thus could in principle image chunks of brain tissue without sectioning.

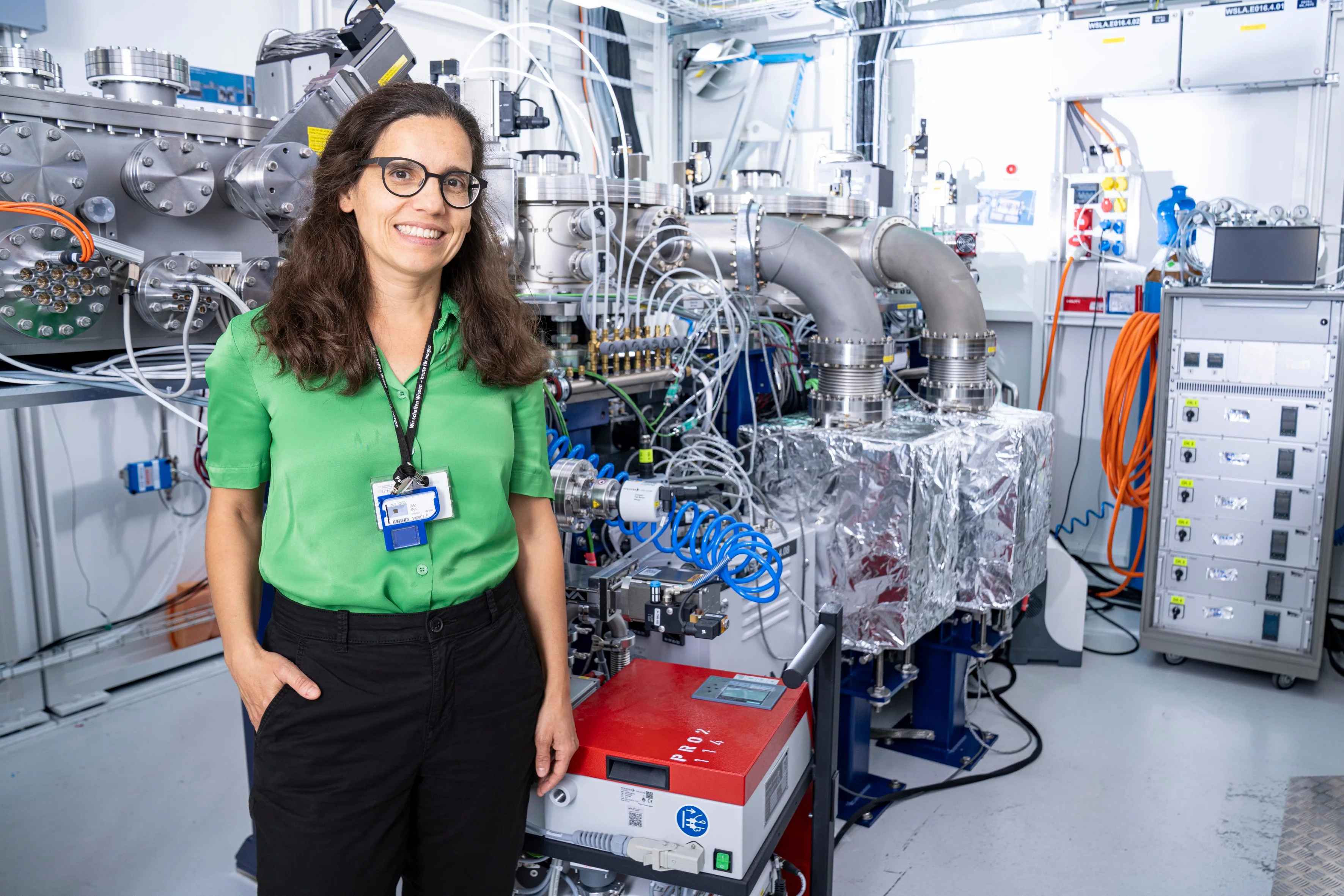

At the coherent small-angle X-ray scattering beamline of the SLS, known for short as cSAXS, high-brilliance X-rays have enabled computer chips to be imaged to a resolution of just 4 nanometres – a world record. “But for biological tissues, the problem is contrast,” explains Ana Diaz, scientist at cSAXS. “Computer chips are made of copper wires that naturally have a high contrast to their embedding material. When we have the building blocks of life – proteins, lipids and so on, against a matrix dominated by water, the X-ray interaction is very weak and it’s harder to achieve high resolution.”

To overcome these challenges of contrast, scientists stain the brain tissue using heavy metals. However, these absorb the X-rays, leading to another problem: the sample deforms. Embedding materials can stabilise the sample – but these also possess the same problems that they deform in the presence of X-rays, bubbling and destroying the fine ultrastructure of the brain tissue.

A resin for the aerospace industry

To overcome this problem, Wanner, Diaz and colleagues came up with a new approach. The main development is an epoxy resin that is still able to infiltrate the biological tissue while offering exceptional radiation tolerance – a material usually used in aerospace and nuclear industries and in particle accelerators.

They complement this with a specially designed stage that allows them to image the samples whilst cooled to –178 degrees Celsius with liquid nitrogen. Finally, a reconstruction algorithm compensates for small amounts of deformation that still do occur.

With this approach, the researchers could study pieces of mouse brain tissue up to 10 microns thick, achieving a resolution of 38 nm in three dimensions. “We believe this marks a record resolution using X-ray imaging on an extended biological tissue,” says Diaz.

At this resolution, they could reliably identify synapses and other features of the neurons and their connections, such as axons and dendrites. “This is not breakthrough information on the brain: it matches the best results with state-of-the-art volume electron microscopy – the current gold standard,” adds Wanner. “What’s exciting is that this marks the start of what’s to come.”

Coherent X-rays set for a boost with SLS upgrade

Although a 10-micron thick piece of brain tissue may still sound tiny, this is already orders of magnitude thicker than the slivers studied with electron microscopy. Currently a limiting factor on sample size is the acquisition time: taking enough data to reconstruct a high-resolution image can take days. This bottleneck is related to the X-rays.

The researchers are using a technique known as ptychography – a type of imaging that doesn’t use lenses but relies on coherent X-rays. “Coherence is exactly where we are set to gain with the SLS upgrade,” says Diaz.

The SLS has just completed a comprehensive upgrade to become a 4th-generation synchrotron – the most advanced type of synchrotron in the world. The technological improvements mean that, at the cSAXS beamline, ptychography experiments will benefit from up to one hundred times higher flux of coherent X-rays.

“With one hundred times more X-ray photons hitting our sample every second, we will be able to – in principle – either image the sample one hundred times faster or image volumes one hundred times larger,” explains Diaz. “In practice, we will need to learn how to do this in an efficient way. But the potential is there.”

The publication coincides with an important milestone at the beamline: in July 2025, the first X-rays were seen at cSAXS following the upgrade. Now that technical barriers to using X-ray ptychography for biological imaging have been overcome, the way lies open to studying much larger samples of brain tissue in 3D at high resolution.

Contact

Original Publication

Non-destructive X-ray tomography of brain tissue ultrastructure

Carles Bosch, Tomas Aidukas, Mirko Holler, Alexandra Pacureanu, Elisabeth Müller, Christopher J. Peddie, Yuxin Zhang, Phil Cook, Lucy Collinson, Oliver Bunk, Andreas Menzel, Manuel Guizar-Sicairos, Gabriel Aeppli, Ana Diaz, Adrian A. Wanner and Andreas T. Schaefer

Nature Methods, 27.11.25 (online)

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2300 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 450 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2025)