For thirty years, experiments conducted at the Center for Nuclear Engineering and Sciences have been providing unique insight into how metals and ceramics degrade under high-energy proton bombardment.

What happens to materials on a microscopic level when they are exposed to extremely harsh radiation conditions? This is the question Paul Scherrer Institute PSI scientist Günter Bauer posed thirty years ago when proposing a new programme at the Swiss Spallation Neutron Source SINQ. Such harsh radiation environments exist in nuclear power plants, research reactors, and also spallation sources – accelerator-based facilities that produce neutrons by firing protons at a heavy metal target. Here, atoms are bombarded by high-energy particles, crystal lattices are shaken apart, and gases such as helium and hydrogen accumulate within the material: the conditions are so extreme that even the strongest metals can slowly lose their strength and integrity.

At the time, though, little was known about how such conditions affect the behaviour of materials – for example, whether they become brittle and whether safety-relevant components remain fit for purpose.

Since its launch, the programme, known as the SINQ Target Irradiation Programme, or STIP, has become a globally unique and indispensable resource for understanding radiation damage in materials. By generating critical data for spallation, fusion, and fission research worldwide, the programme allows accurate prediction of component lifetimes, thus helping to ensure the safe operation of nuclear facilities.

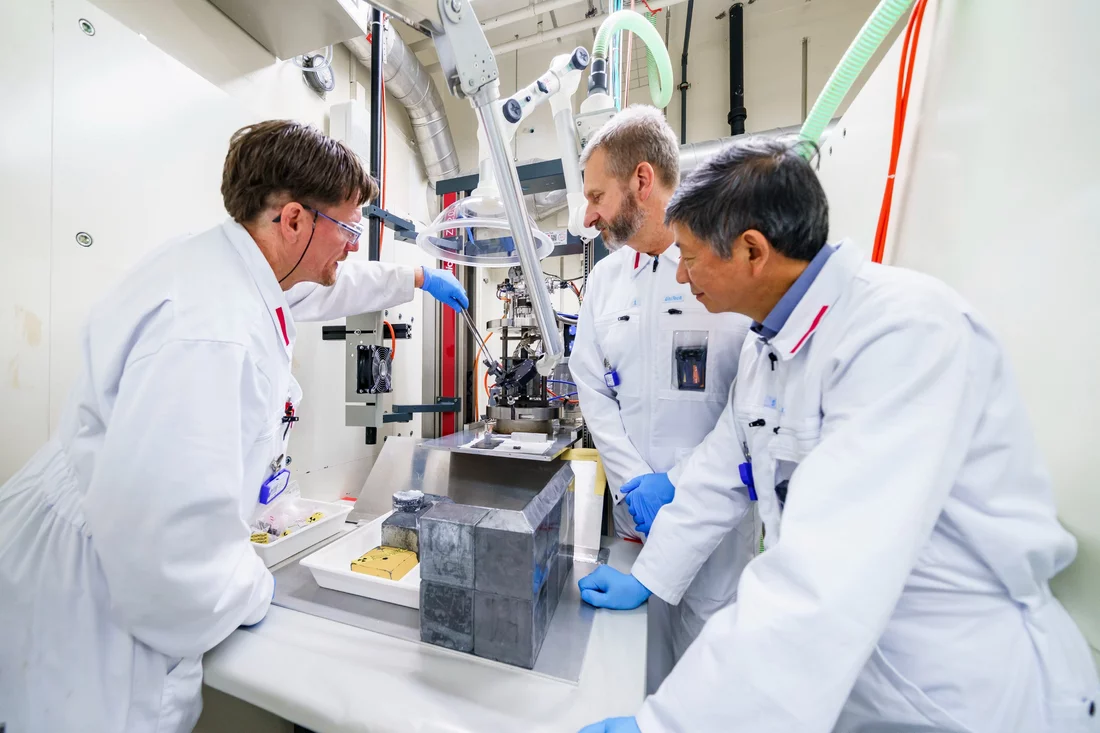

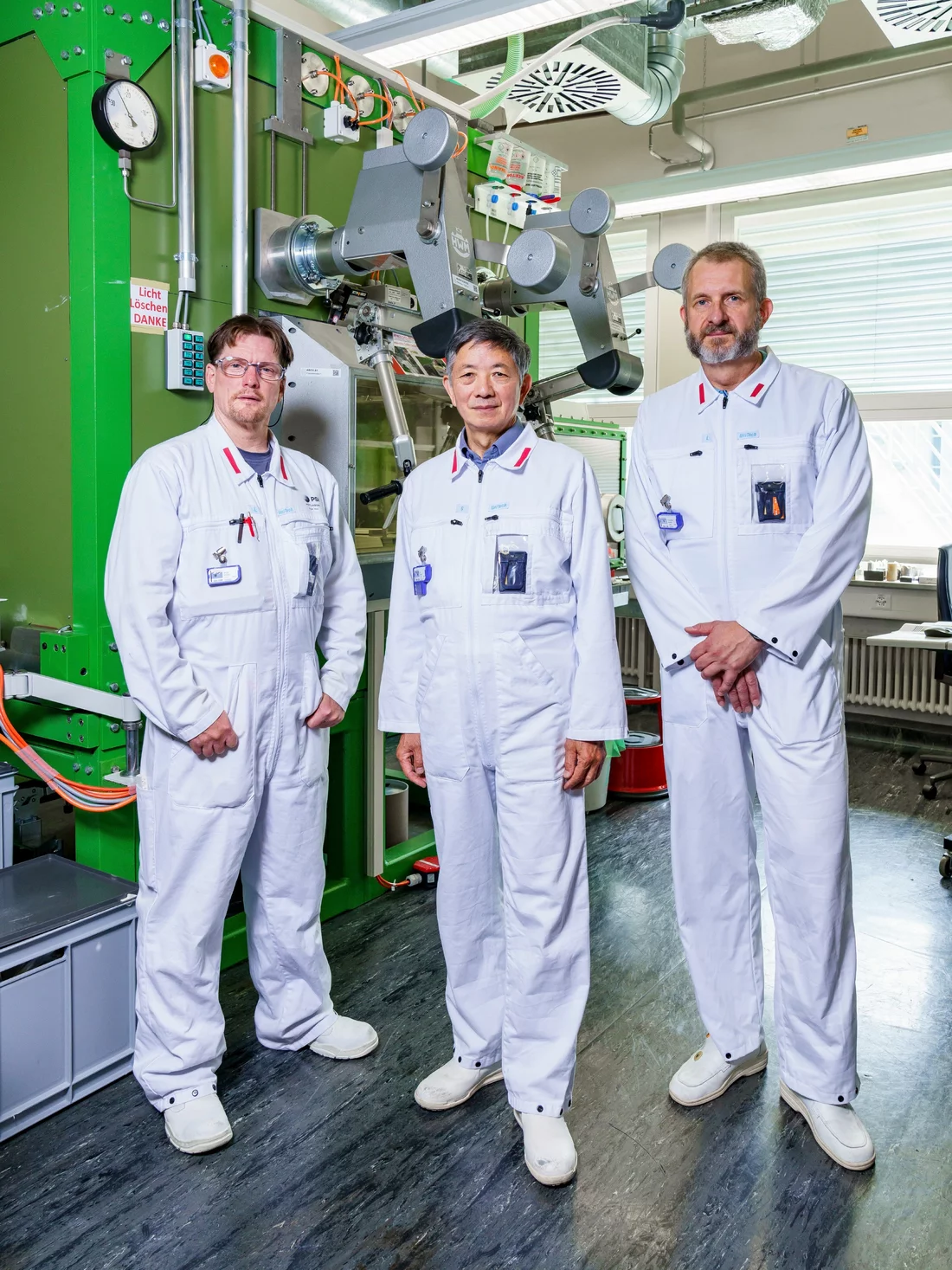

STIP has been led for nearly three decades by Yong Dai of PSI’s Laboratory for Nuclear Materials. Since STIP was launched, Dai’s team has irradiated over 9,000 samples to the highest levels ever reached in spallation targets in the world. The workload was, Dai says, “immense.” Furthermore, Dai explains, handling highly activated samples is no easy task: "In particular, given the strict safety measures that this type of work requires.” Reflecting on the project, Dai emphasises that “the uniqueness of STIP, the constructive collaborations, and the scientific discoveries have motivated me to work tirelessly for so many years.”

A unique approach to irradiation testing

STIP stands as a globally unique platform for testing materials under extreme conditions. Each STIP experiment is a complex, multi-year endeavour that unfolds over four distinct phases: planning, irradiation, extraction, and finally, post-irradiation examination. These four phases span at least seven years.

For irradiation, small material specimens are encapsulated in metal rods designed to fit into the target assembly. The materials to be irradiated, provided primarily by research institutes and industrial partners, include structural alloys (based on iron, nickel, aluminium, zirconium and molybdenum), ceramics such as silicon carbide, and functional metals like tungsten and tantalum. These are used in applications ranging from spallation sources and accelerator-driven systems to fusion and fission research projects.

“Compared to a research reactor, where such questions are normally addressed, STIP is a relatively small-scale but extremely smart approach,” explains Manuel Pouchon, head of the Laboratory for Nuclear Materials. STIP exposes materials to both the protons from the accelerator and a broad spectrum of spallation neutrons generated in the target itself. This contrasts with materials testing at fission reactors, which produce mainly low-energy neutrons.

This combination of protons and neutrons makes it possible to study multiple degradation mechanisms simultaneously, such as displacement damage, helium and hydrogen accumulation, and, where relevant, liquid metal corrosion. The combined damage caused by these different effects is greater than the sum of their individual contributions – a phenomenon known as synergistic amplification. The effects of such interactions remain an important topic of scientific inquiry.

After the target has been operating for about two years, the specimens have experienced exceptionally high levels of damage. The post-irradiation examination aims to answer how the materials behaved under such extreme conditions, whether they can be used in similar environments, and if so, for how long.

Thirty years on, the importance of STIP continues

Today, the irradiation behaviour of materials employed in fission reactors under operating conditions is well characterised. However, new materials combined with technological advancements make additional study necessary before changes to a nuclear system can be implemented. This is essential for the safety of these systems.

Moreover, the research deepens fundamental understanding of irradiation behaviour, introducing new mechanisms and experimental data, which can also be used to further develop modelling tools and validate them.

Recognized as one of the leading programmes for understanding materials’ behaviour under irradiation and defining safety margins, STIP provides data that support the design and safe operation of spallation sources and fusion reactors worldwide. For example, research institutions and universities across Europe, the USA, Japan, and China rely on STIP to evaluate target performance and predict component lifetimes.

The experimental conditions made possible by STIP are essential for developing future nuclear systems, such as accelerator-driven systems whose main goal is the transmutation of nuclear waste. The Swiss spin-off company Transmutex, for example, collaborates with the STIP team. With the current phase of STIP approaching completion, efforts are focused on ensuring its continuation and further development to address future research challenges. This could lead to significant advancements in materials research, allowing PSI to continue to serve as a pivotal resource for understanding material behaviour under extreme conditions, and thereby supporting the ongoing evolution of nuclear systems.

To learn more about STIP, visit: https://www.psi.ch/en/lnm/sinq-target-irradiation-program-stip