Our universe consists of significantly more matter than existing theories are able to explain. This is one of the great puzzles of modern science. One way to clarify this discrepancy is via the neutron’s so-called electric dipole moment. In an international collaboration, researchers at PSI have now devised a new method which will help determine this dipole moment more accurately than ever before. They report on it in the journal Physical Review Letters on 16nd October 2015.

Researchers in an international collaboration at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) have successfully developed a new experimental method to determine a fundamental property of the neutron. Neutrons are parts of atomic nuclei, and thus key building blocks in the matter that surrounds us. Although they are so omnipresent, some of their properties still have not been understood adequately – including the neutron’s so-called electric dipole moment. The dipole moment has far-reaching consequences for our understanding of the universe: it might help explain why considerably more matter than antimatter was formed during the Big Bang.

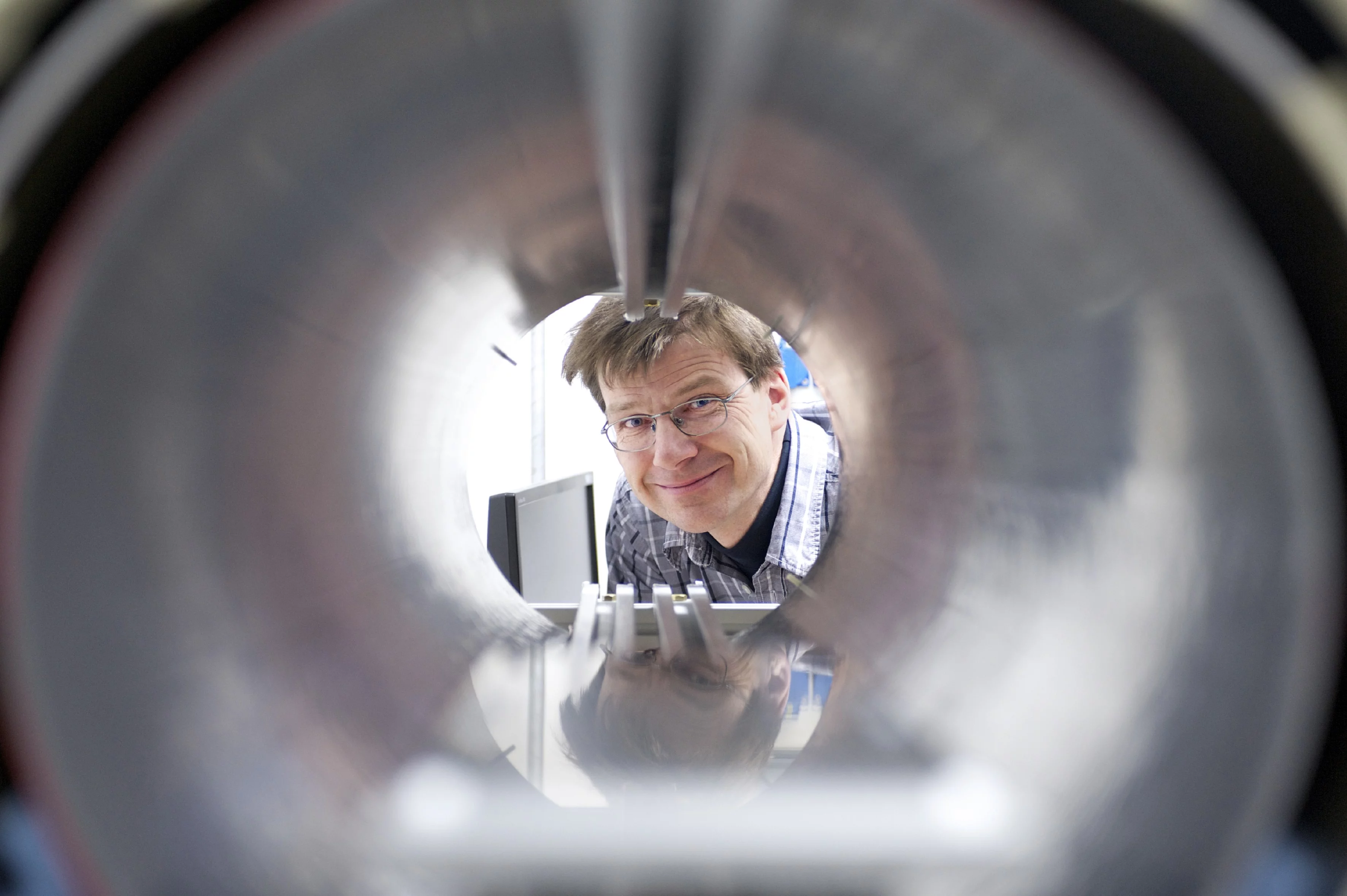

Philipp Schmidt-Wellenburg from PSI and his colleagues devised the co-called spin-echo method to measure slow, freely moving neutrons. Consequently, they have created a new, non-destructive imaging technique for the high-precision measurement of neutron velocity.

Compensating any disturbance for minutes at a time

Schmidt-Wellenburg uses the analogy of a race over unknown terrain to explain the method’s basic principle: We send neutrons – our ‘runners’ – off with a kind of starting shot. After a certain time, we turn them around with a second signal.

All the neutrons then return to the starting point like an echo. The different time delay at which the individual neutrons cross the finish line tells the researchers something about the nature of the space they each ran

through: Similarly, in a group of equally sporty runners, if one made it back later than the rest, it would suggest that there were more obstacles on their course.

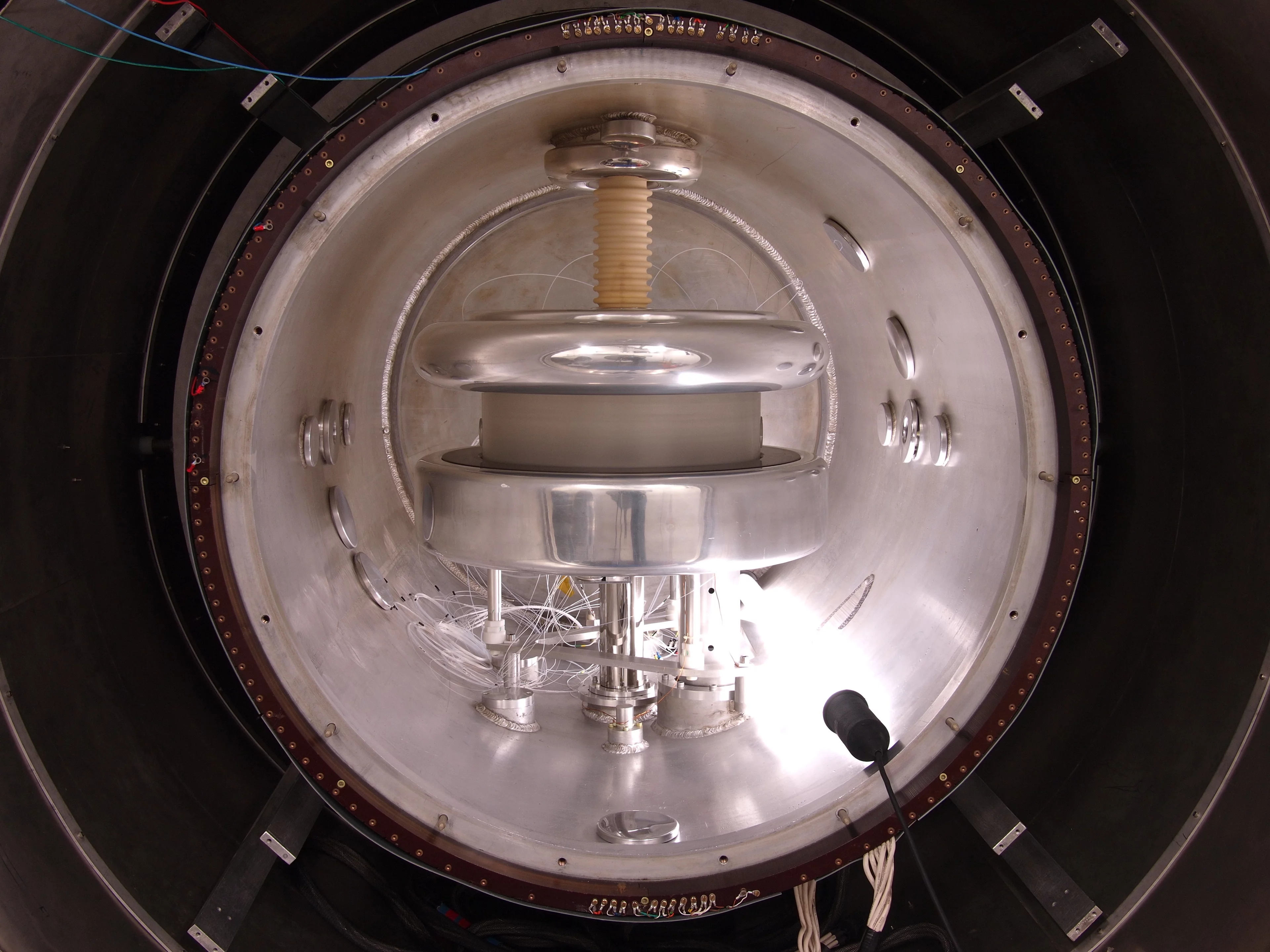

In principle, the spin-echo method is nothing new. In medicine, it has been used for decades in magnetic resonance imaging for tissue and organs. The difference and thus the main challenge with the new method: the neutrons used here are extremely slow and observed for minutes at a time. Such slow neutrons are also dubbed ultra-cold neutrons. Using them, however, means that all the experimental framework conditions need to be kept extremely stable for comparatively long periods of several minutes. Just to illustrate the degree of precision involved in the experiment: We have to balance out even tiny changes in the magnetic field, which can even come about if a lorry drives past on the nearby road, for instance,

explains Schmidt-Wellenburg.

Measurements with the new method are already underway

All this is necessary to determine the neutron’s electric dipole moment with greater precision than ever. The last experiment to measure this factor to date was published in 2006. However, the result from back then is still too unprecise to draw any conclusions regarding the origins of the universe from it. Since then, there has been a lack of methods for a more accurate measurement. Now we’ve plugged this gap with our adapted spin-echo method for ultra-cold neutrons,

says Schmidt-Wellenburg.

Measurements of ultra-cold neutrons using the new method have been underway at PSI since August 2015. The institute boasts one of the most intense sources of ultra-cold neutrons in the world. The local long-term experiment will have to continue for about another year to obtain the amount of data needed to determine the neutron’s electric dipole moment more precisely than in previous measurements. Hopefully, one day we will then be able to explain why our universe is made up of so much matter – in other words, why all the matter and antimatter failed to destroy each other shortly after the Big Bang,

says Klaus Kirch, Head of the Laboratory of Particle Physics at PSI.

The new spin-echo method with ultra-cold neutrons can also be used for other fundamental experiments, such as measuring the lifespan of neutrons more accurately. I dare say that our new method will be used in many experiments with ultra-cold neutrons in the next twenty years,

ventures Schmidt-Wellenburg.

Text: Paul Scherrer Institute/Laura Hennemann

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 1900 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 380 million.

(Last updated on April 2015)

Additional information

Search for the neutron electric dipole moment at PSIContact

Dr. Philipp Schmidt-Wellenburg, Laboratory for Particle Physics, Paul Scherrer Institute,telephone: +41 56 310 56 80, e-mail: philipp.schmidt-wellenburg@psi.ch

Prof. Dr. Klaus Kirch, Laboratory for Particle Physics, Paul Scherrer Institute,

telephone: +41 56 310 32 78, e-mail: klaus.kirch@psi.ch

Original Publication

Observation of gravitationally induced vertical striation of polarized ultracold neutrons by spin-echo spectroscopyS. Afach, N.J. Ayres, G. Ban, G. Bison, K. Bodek, Z. Chowdhuri, M. Daum, M. Fertl, B. Franke, W.C. Griffith, Z.D. Grujic, P.G. Harris, W. Heil, V. Hélaine, M. Kasprzak, Y. Kermaidic, K. Kirch, P. Knowles, H.-C. Koch, S. Komposch, A. Kozela, J. Krempel, B. Lauss, T. Lefort, Y. Lemière, A. Mtchedlishvili, M. Musgrave, O. Naviliat-Cuncic, J.M. Pendlebury, F.M. Piegsa, G. Pignol, C. Plonka-Spehr, P.N. Prashanth, G. Quéméner, M. Rawlik, D. Rebreyend, D. Ries, S. Roccia, D. Rozpedzik, P. Schmidt-Wellenburg, N. Severijns, J.A. Thorne, A. Weis, E. Wursten, G. Wyszynski, J. Zejma, J. Zenner, and G. Zsigmond,

Physical Review Letters 16 October 2015

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.162502