Microtubules perform an active role in communication within the cell by transmitting received signals to the cell's functional units. Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel have now, for the first time, structurally elucidated how these protein strands of the cytoskeleton accomplish this. Their findings could help make it possible to intervene in this communication and, for example, prevent tumour growth. The study was published in the scientific journal Cell.

The most diverse functions of a cell in the human body – from cell division and differentiation to motility and programmed cell death – are controlled by signalling proteins within the cell. This includes the immune system and the reading of genetic information. Initially the commands come from outside the cell, via hormones, cytokines, or growth factors; they reach the cell membrane, bind to corresponding receptors, and are then translated into signalling proteins that transmit commands to the cell's interior. The signal then reaches the microtubules through several stages.

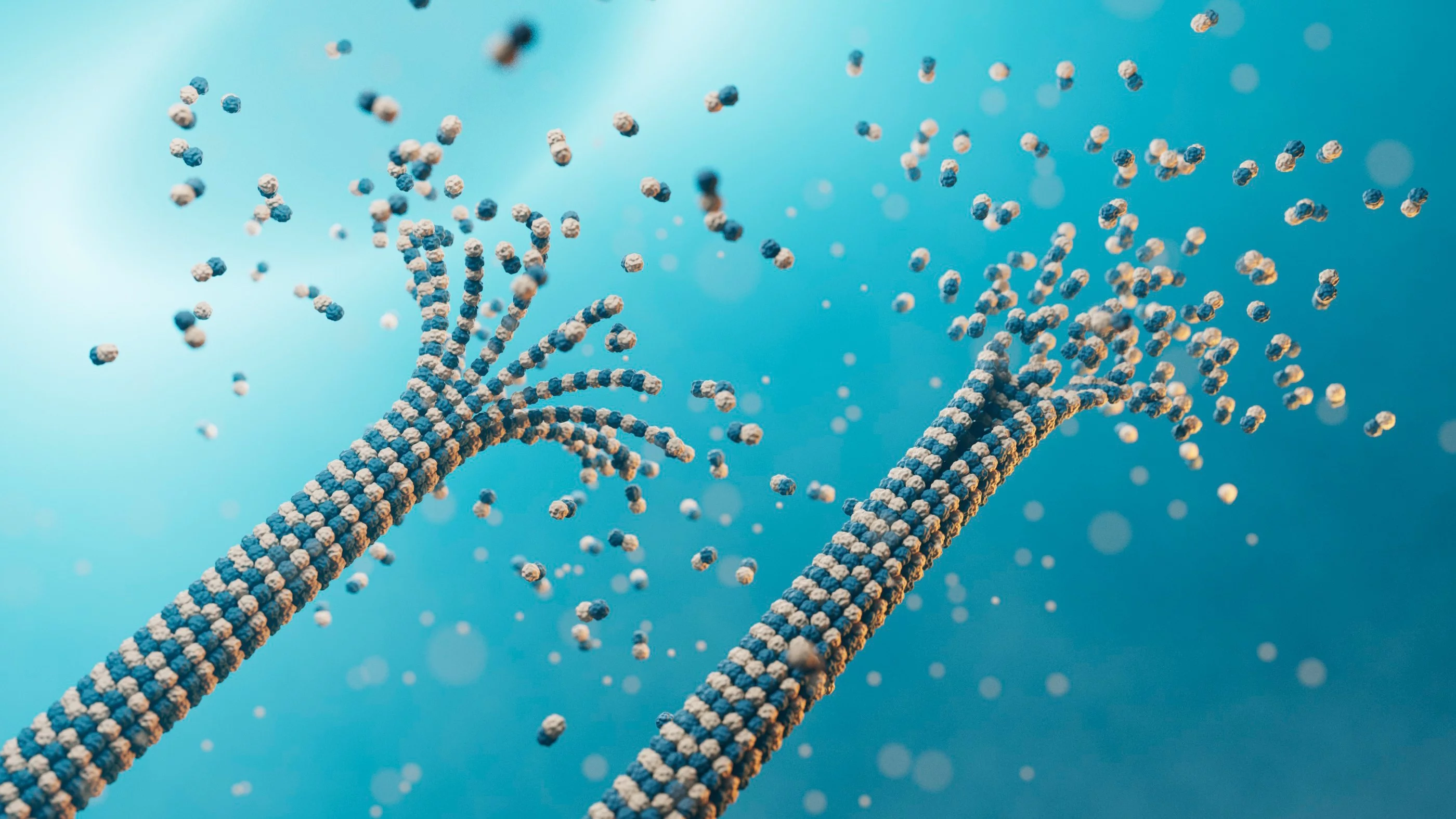

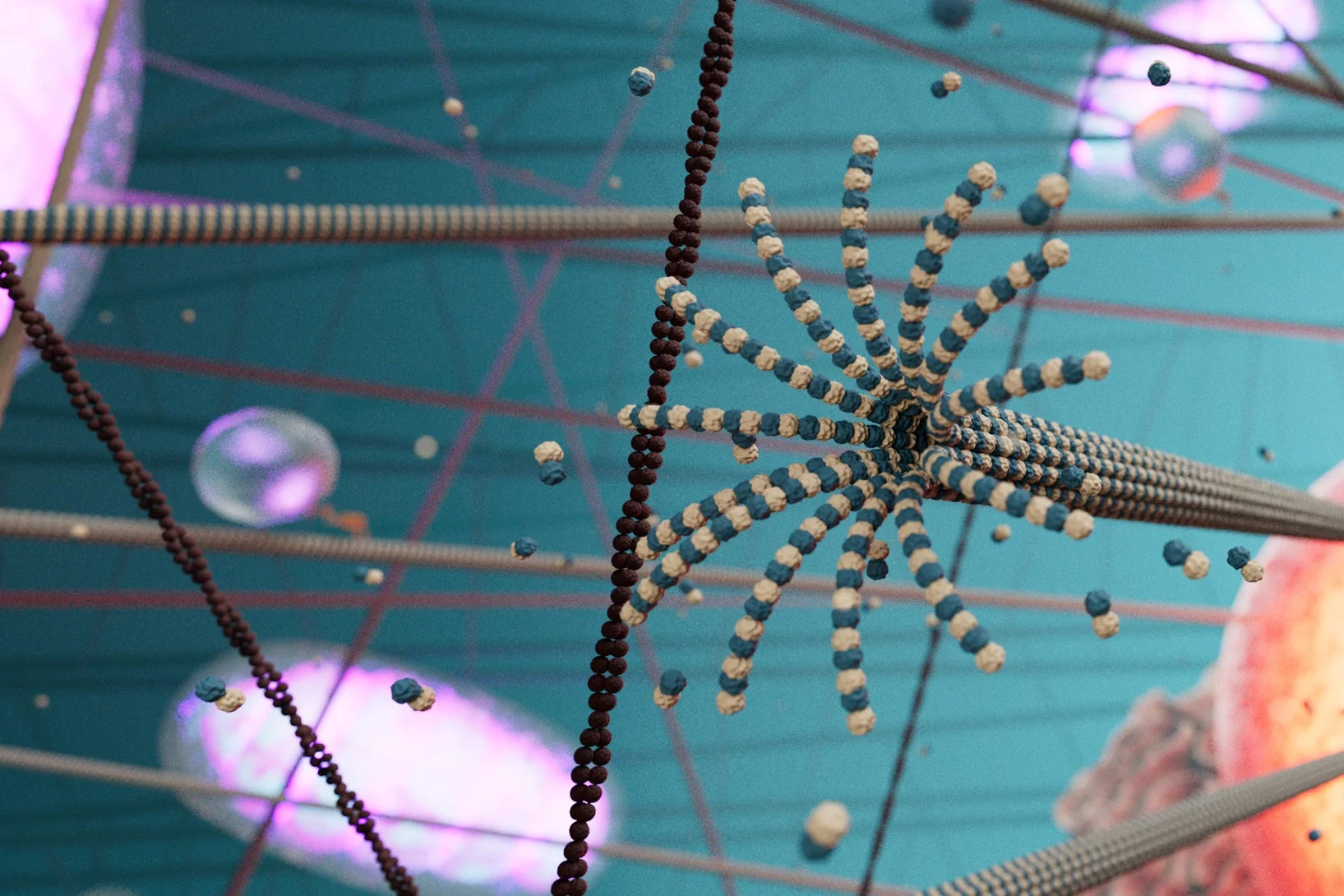

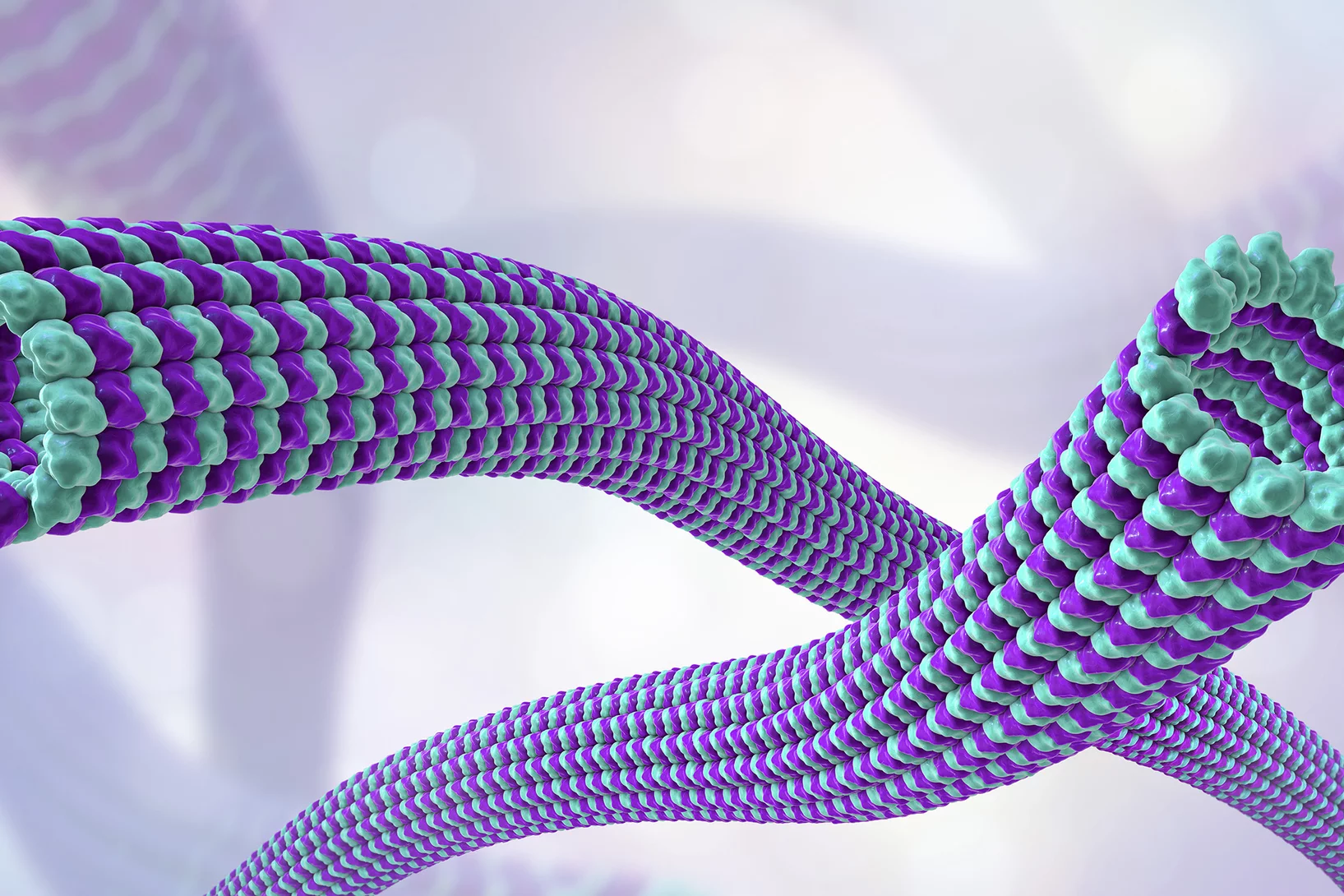

Microtubules are central protein strands of the cytoskeleton. Much as the human body is supported by its skeleton of bones, the cell is supported by the cytoskeleton. However, the cytoskeleton also performs other functions. If we think of the cell as a city, microtubules form the main roads, so to speak, connecting the important structures (corresponding to organelles such as the nucleus, mitochondria, and ribosomes) and enabling the transport of goods (biomolecules) between them.

The difference is that microtubules are dynamic: They constantly form new connections and dismantle old ones thereby rearranging themselves. It was previously thought that microtubules were merely receivers in the context of cell signalling that responded to such commands by altering their dynamics and their organisation. But in fact they also fulfil the function of transmitting signals to other receivers. When such a protein docks, they activate signalling pathways for certain cellular functions, such as immune defense and cell division, which are of fundamental importance to the organism. If they did not do this, certain commands would not reach their destination, and the cells would not function. Studies demonstrated this several decades ago.

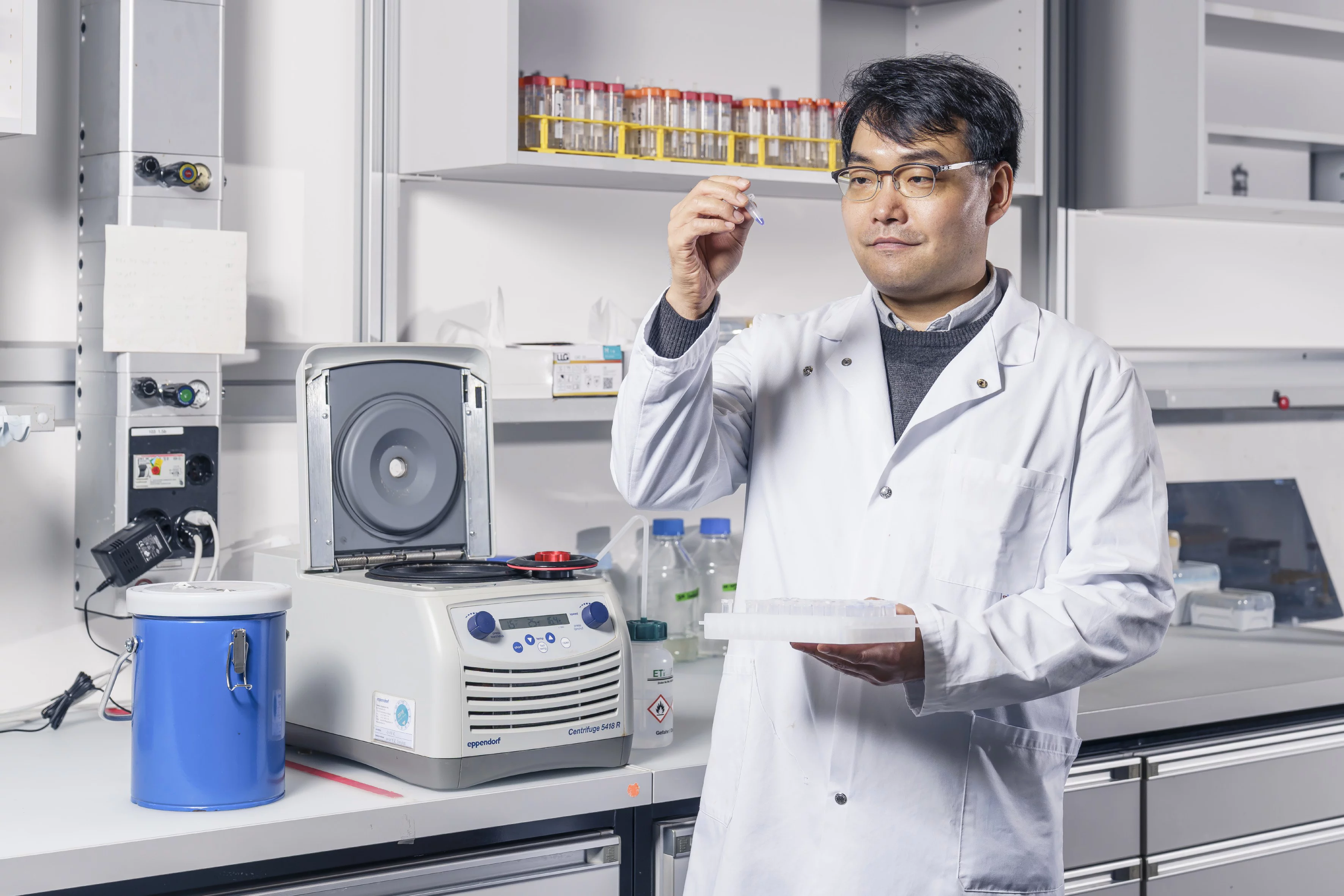

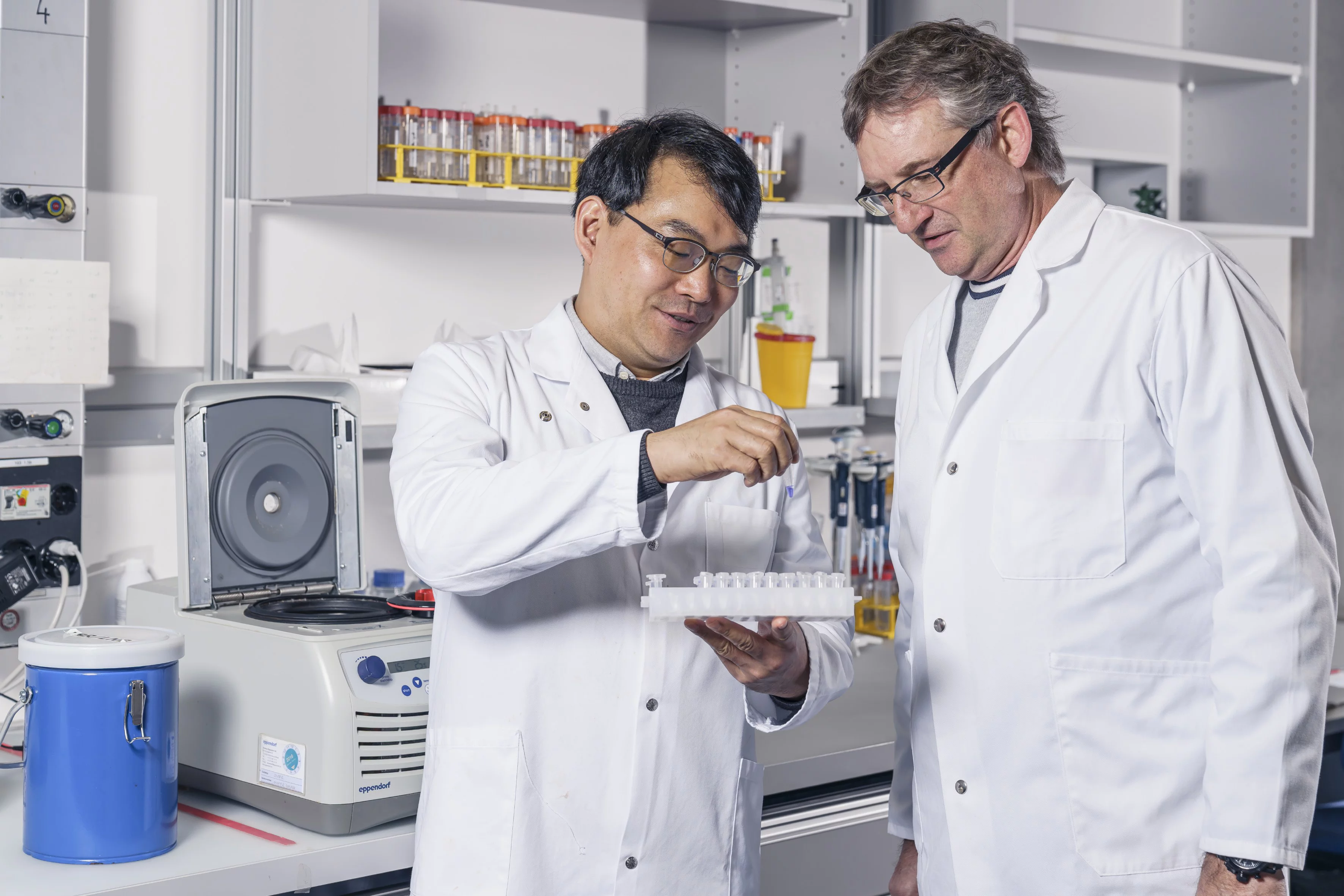

Until recently, however, it remained unclear how this transmission of signals through the microtubules occurs at the molecular level. A team from the PSI Center for Life Sciences, led by lead author Sung Choi and project leader Michel Steinmetz, has now elucidated this using a signalling protein called GEFH1 – in close collaboration with the research group of Alfred Zippelius at the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel.

How the process works

GEFH1 stands for guanine nucleotide exchange factor H1, which is a thoroughly studied signalling protein that activates the so-called RhoA signalling pathway. This signalling pathway alone – and it is just one of many – triggers an entire cascade of cellular processes that control functions including cell division and cell motility, so that it can for example participate in wound healing.

Hormones: Endogenous substances that transmit information from one cell to another. They regulate functions including energy and water balance, growth, and reproduction.

Cryo-electron microscopy: An important tool for biological structural analysis, in which samples are flash-frozen and can be examined at almost atomic resolution.

Organelles: These functional units perform certain tasks within the cell, similar to the way organs perform tasks in our bodies. Organelles include the cell nucleus, mitochondria, and ribosomes.

Mitochondria: These organelles are often called the power plants of cells, converting nutrients into energy.

Ribosomes: These complexes of especially large molecules are, so to speak, the protein factories of the cell: They produce various proteins on the basis of genetic information contained in the nucleus.

Growth factors: These messenger substances carry information from one cell to another and regulate cell growth and differentiation, that is, which bodily function a cell will later assume.

Cytokines: These are also messenger substances that migrate from cell to cell. They primarily regulate the immune system and activate the production of defense cells.

Once GEFH1 reaches the microtubules, it docks and is inactivated. Using cryo-electron microscopy, biochemical, and cell biological studies, the PSI team has now been able to demonstrate that this binding occurs only through a very specific molecular part of the protein consisting of many amino acids, the so-called C1 domain. “We bioengineered and tested fragments of GEFH1 that are capable of binding to microtubules,” Sung Choi reports. “We constructed variants of GEFH1 with mutated docking sites and introduced them into cells to see if they would bind. This allowed us to clearly establish that the C1 domain alone is responsible for the binding.” This is the case with exactly four tubulins – the special proteins that make up the strands of the microtubule. GEFH1, with its C1 domain, fits into a recess between them, like a plug in a suitable hole. This was revealed by the cryo-electron microscope.

The signalling protein is released when the microtubule unravels as part of its normal dynamics and the tubulin strand breaks apart at the site where it is located. This activates the RhoA signalling pathway to initiate further cellular processes.

New tool for medicine

The results of the study serve mainly to improve the fundamental understanding of cellular processes. “They complete our picture of the signalling cascades triggered in the cell by messenger substances such as hormones and cytokines,” says Michel Steinmetz. “As an active element in this mechanism, microtubules assume an even greater significance.” Furthermore, a more precise understanding of these processes offers us new possibilities in medicine. There are already ways to block receptors for certain signalling proteins on the cell membrane, to prevent proliferative cell growth in cancer for example or, in other cases, to promote binding and thus strengthen the immune system. Now such intervention options could possibly be developed at the level of the C1 domain and the microtubules. “We would then have an additional tool to intervene to address malfunctions,” says Sung Choi.

This finding can probably be transferred to many other signalling proteins and pathways: “Other signalling proteins – and there are countless others besides GEFH1 – have a different structure,” Michel Steinmetz explains. “But many of them, similarly, have a C1 domain with which they bind to the microtubules.” Thus the number of options for medical intervention based on blocking or promoting C1 domain binding could be correspondingly vast. One particularly relevant example is the tumour-suppressing protein RASSF1A, whose interaction with microtubules via the C1 domain was also demonstrated in the course of this study. RASSF1A is one of the prototypical tumour suppressor genes and is frequently inactivated in more than 40 types of human malignancies, including lung, breast, prostate, glioma, neuroblastoma, multiple myeloma, and kidney cancer. This further underscores the therapeutic relevance of the C1 domain mechanism.

However, there are also signalling proteins that bind to microtubules without having a C1 domain. “How they do this is something we want to find out in further studies,” says Michel Steinmetz. “To that end, we have developed a pipeline of tests and procedures that can be transferred to the task of tracking down additional mechanisms.”

Contact

Prof. Dr. Michel Steinmetz

Head a.i. Center for Life Sciences

Paul Scherrer Institute PSI

Original publication

Structural basis of microtubule-mediated signal transduction

Sung R. Choi et al.

Cell, 8.12.2025

More articles on this topic

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2300 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 450 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2025)