Reorganisation of the brain and sense organs could be the key to the evolutionary success of vertebrates, one of the great puzzles in evolutionary biology, according to a paper by an international team of researchers, published today in Nature.

The study claims to have solved this scientific riddle by studying the brain of a 400 million year old fossilized jawless fish – an evolutionary intermediate between the living jawless and jawed vertebrates (animals with backbones, such as humans).

Palaeontologists and physicists from the University of Bristol (UK), the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP, China), Museum national d'Histoire naturelle (Paris, France) and the Paul Scherrer Institut (Switzerland) collaborated to study the structure of the head of a primitive fossil jawless fish called a galeaspid.

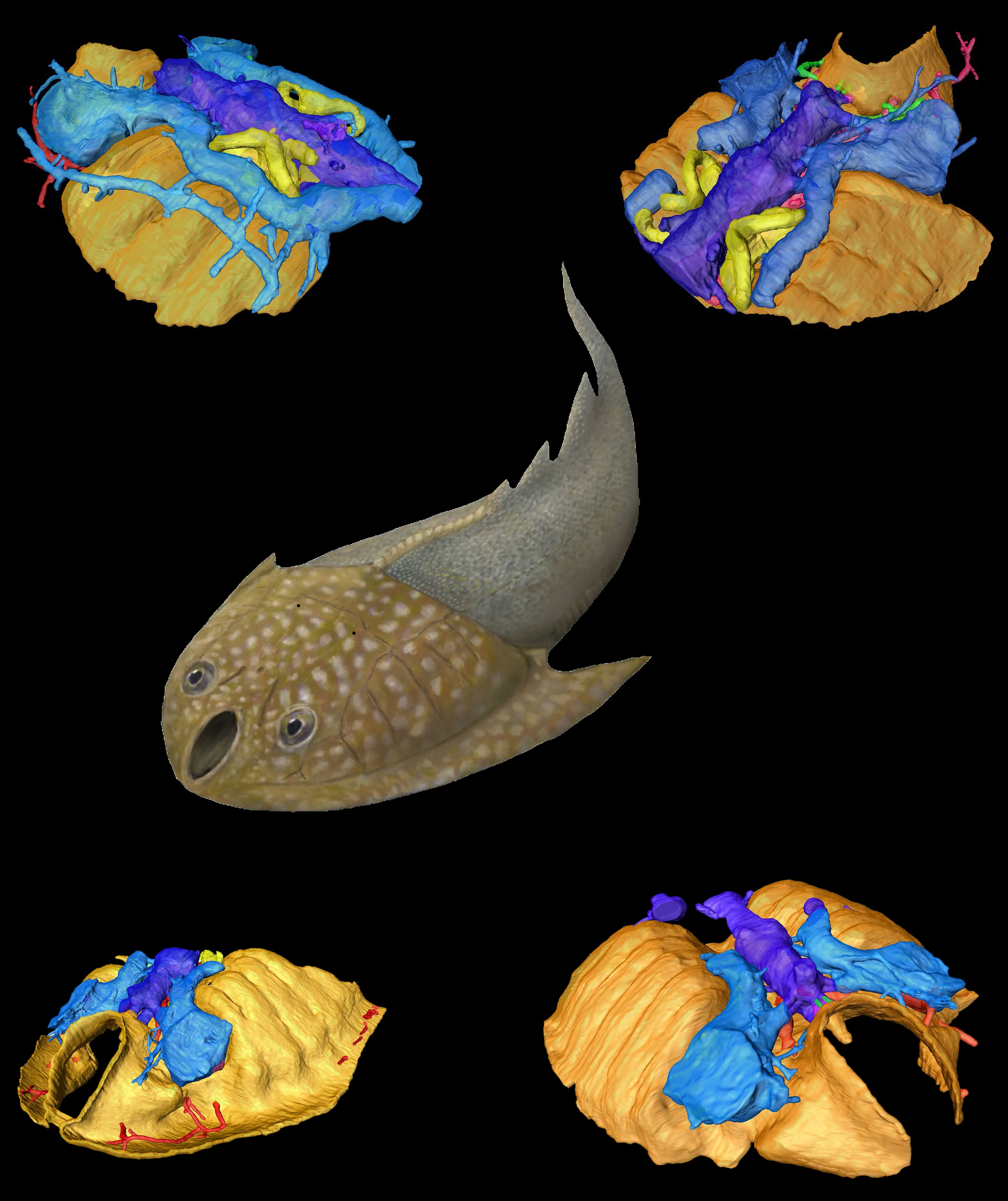

Instead of breaking the fossil up, they studied it using high energy X-rays at the Swiss Light Source in Switzerland, revealing the shape of the animal's brain and sense organs.

Lead author, Gai Zhi-kun of the University of Bristol and the IVPP, China, said We were able to see the paths of all the veins, nerves and arteries that plumbed the brain of these amazing fossils. They had brains much like living sharks – but no jaws.

The origin of a mouthful of jaws and teeth is one of the biggest steps in our evolutionary history but fossils have not provided any insights – until now.

Zhi-kun continued: We've been able to show that the brain of vertebrates was reorganised before the evolutionary origin of jaws.

Co-author, Professor Philip Donoghue of the University of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences said: In the embryology of living vertebrates, jaws develop from stem cells that migrate forwards from the hindbrain, and down between the developing nostrils. This does not and cannot happen in living jawless vertebrates because they have a single nasal organ that simply gets in the way.

Professor Min Zhu of IVPP continued: This is the first real evidence for the steps that led to the evolutionary origin of jawed vertebrates, and the fossil provides us with rock solid proof.

Professor Philippe Janvier of the Museum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris, said: This research has been held back for decades, waiting for a technology that will allow us to see inside the fossil without damaging it. We could not have done this work without this crazy collaboration between palaeontologists and physicists.

Professor Marco Stampanoni of the Paul Scherrer Insitut, the location of the Swiss Light Source said: We used a particle accelerator called synchrotron as X-ray source for performing non destructive 3D microscopy of the sample. It allowed us to make a perfect computer model of the fossil that we could cut up in any way that we wanted, but without damaging the fossil in any way. We would never have got permission to study the fossil otherwise!

This work was funded by the Royal Society, the Natural Environment Research Council, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Foundation of Natural Sciences, EU Framework Programme 7, and the Paul Scherrer Institut.

Scientists involved:

Zhi-kun Gai is a PhD student at the School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK and a Researcher at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeonanthropology, Beijing, P. R. China.

Professor Philip Donoghue is Professor of Palaeobiology in the School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK

Professor Min Zhu is Professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeonanthropology, Beijing, P. R. China.

Professor Philippe Janvier is a CNRS Principal Researcher at the Museum national d'Histoire naturelle Paris, France.

Professor Marco Stampanoni is Head of the X-ray Tomography Group at the Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland and Assistant Professor for X-ray Microscopy at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering of the University and ETH Zürich.

Contacts

Original publication

-

Gai Z, Donoghue PCJ, Zhu M, Janvier P, Stampanoni M

Fossil jawless fish from China foreshadows early jawed vertebrate anatomy

Nature. 2011; 476(7360): 324-327. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10276

DORA PSI

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2300 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 450 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2025)