In the year 2001, the Swiss Light Source SLS first went into operation. Since then, the large research facility has been available to a broad international community in Switzerland and worldwide. The facility is getting the upgrade SLS 2.0 so that in the future as well, researchers will find a facility here that meets their needs.

The Swiss Light Source SLS delivers special beams of light for research. It is extremely bright X-ray light, suitable for many different types of investigations, for example in the fields of physics, materials science, biology, chemistry, environmental sciences or for archaeological finds.

Research at SLS

There are around 20 experiment stations at the facility, which are equipped with world-leading instruments. At some of the so-called beamlines, the structure of proteins is being deciphered; at others, researchers can look inside materials with nanometre or even higher precision and in 3-D. At others still, it is possible to explore how the electrons in solid matter behave and how, as a result, magnetism or superconductivity arises.

How synchrotron light is produced

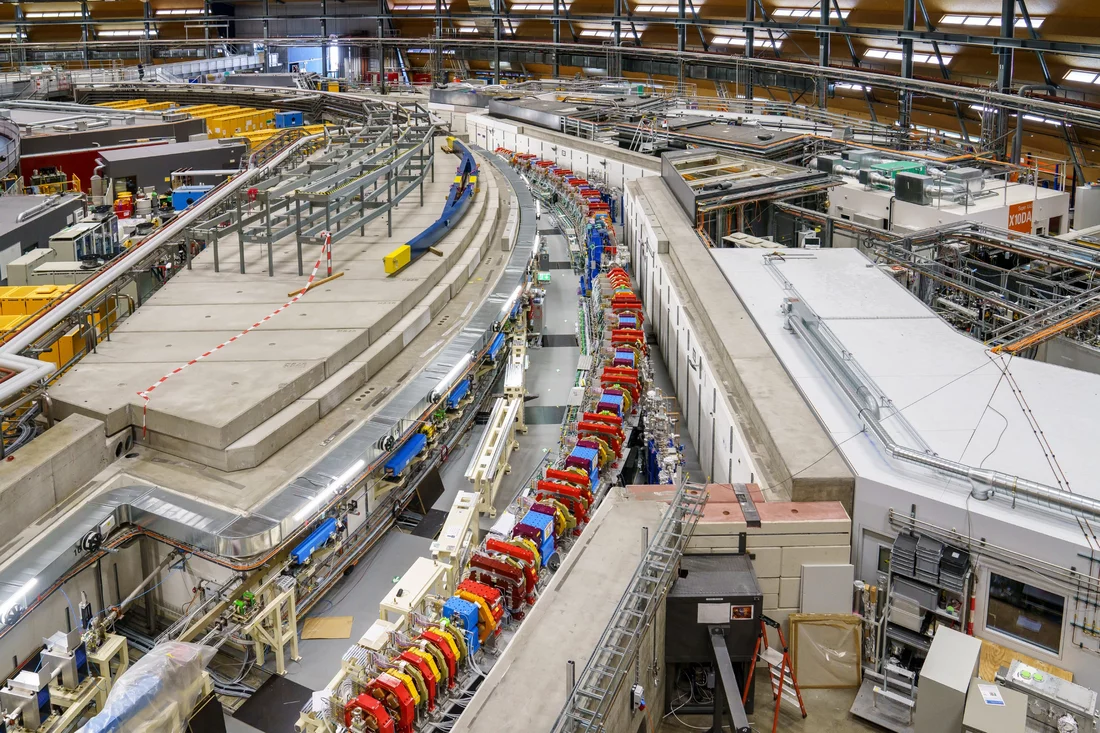

The special light of SLS is generated with the help of electrons accelerated to very high speed: The SLS building houses a so-called electron storage ring. Here, well protected behind thick concrete walls, a metal tube runs in a circle. The tube is connected to strong pumps that suck all the air out of it and thus create a vacuum. Electrons – unimaginably tiny, negatively charged elementary particles – are first brought up to a high speed in an accelerator and then guided into this tube. There they race, at 99.999998 percent of the speed of light, around a circle with a circumference of 288 metres. In other words: Per second, every electron flies a million laps around the storage ring.

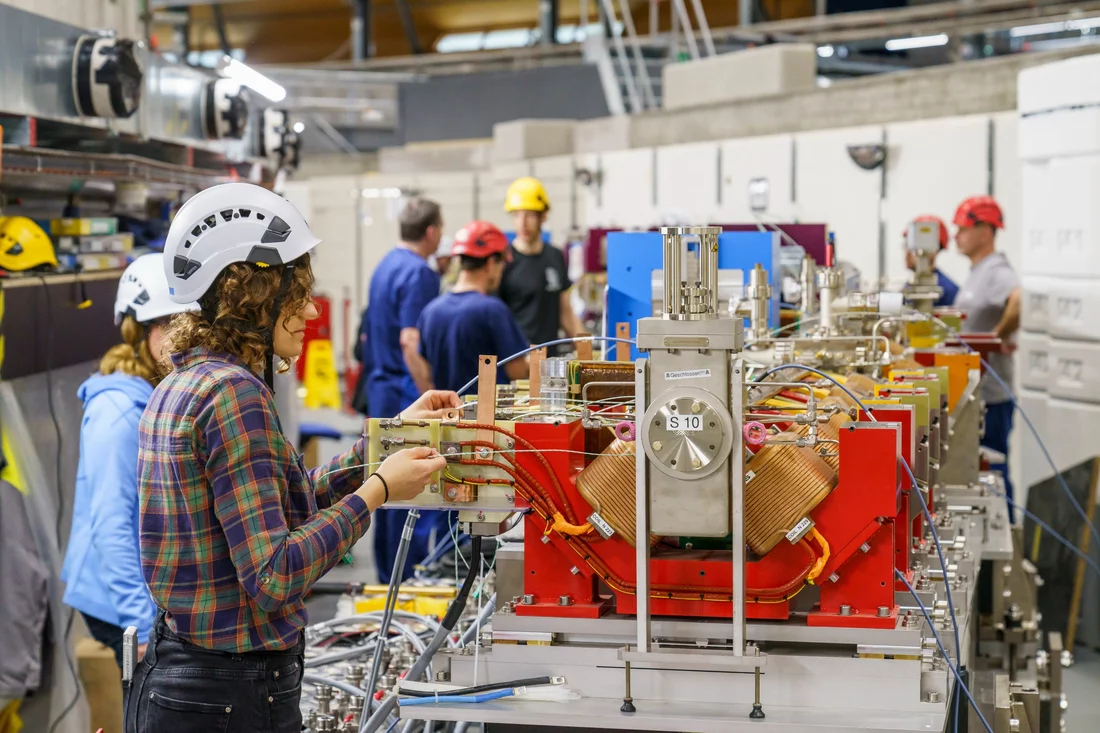

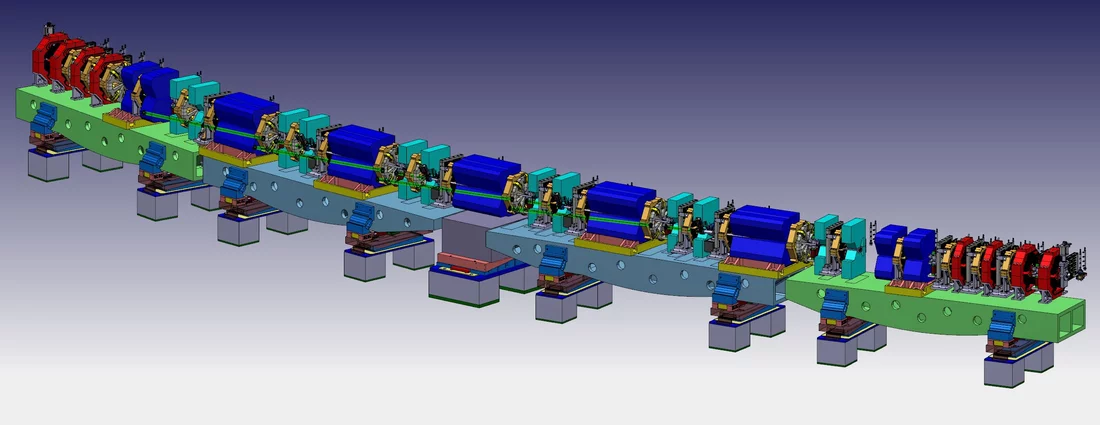

The electrons are held on this circular path by special magnets. These components – which vary from the size of a shoe box up to that of a packing box – surround the tube in many places along the storage ring. These magnets impart a change of direction to the trajectory of the electrons. The characteristics of the magnets determine, in each case, how strongly the electrons are redirected. Strictly speaking, the electrons do not fly a perfectly circular path, but rather are deflected so often that they fly along a polygon.

Some of the magnets also have a further task: Here the X-ray light, which is automatically generated by electrons at every change of their direction and thus in every curve, is guided from the electron storage ring to the experimental stations. This X-ray light is also called synchrotron light.

The goal

The quality of the synchrotron light depends to a large extent on the details of the electrons’ path in the storage ring. In practice, although tight curves create beams that are useful for research, a large number of more modest direction changes, which collectively yield smoother curves, generate qualitatively better beams for the researchers – that is, above all, brighter beams. In other words, the multi-sided polygon of the electron storage ring should become an "even-more-sided" polygon.

This change is the heart of the SLS 2.0 upgrade: It will incorporate significantly more magnets than before, each of which modifies the previous electron path with its relatively large angles into one with many small angles.

The challenge – and the solution

Accommodating still more magnets along the storage ring, which was already equipped with around 100,000 control instruments – for temperature, magnet currents, vacuum pressure, and the like – is the biggest challenge of the SLS 2.0 project.

Solving this problem requires a whole series of measures:

To make room for more magnets, each magnet must first be smaller. However, for a given separation between the north and south poles, smaller magnets provide a weaker effect on the electron beam. To still achieve the necessary field strength, the new magnet components must therefore be placed closer to the path of the electrons. For that, the original diameter of the storage ring tube was too large. A narrower tube needed to be installed. But it is much more difficult to suck the air out of a very narrow tube to create the necessary vacuum quality. To address this problem, in turn, the inner surface of the new tube has a special coating, a so-called non-evaporable getter coating. This absorbs gas atoms permanently and thereby achieves the crucial step in improving the quality of the vacuum.

SLS after the upgrade

All of these measures will lead to a synchrotron beam that ultimately arrives at the SLS experiment stations with around 40 times better values than before. This means that the cross-section of the beam shrinks, so the beam becomes even finer with the same intensity. It will also be even more highly collimated and will scarcely broaden even after several metres. The examination of very small samples, among other things, will benefit greatly from this.

On 30 September 2023, SLS was shut down for the major renovations of the upgrade project SLS 2.0. Thus began the 15-month “Dark Time” at the large research facility.

This “Dark Time” came to an end in January 2025, when the electrons started circulating in the new storage ring. Since then, upgraded beamlines have been receiving X-ray light again, and experiments restarting. The new SLS will be inaugurated on the 21 August 2025.

News

ReMade@ARI Call Announcement

ReMade@ARI is happy to announce a new rolling submission scheme!

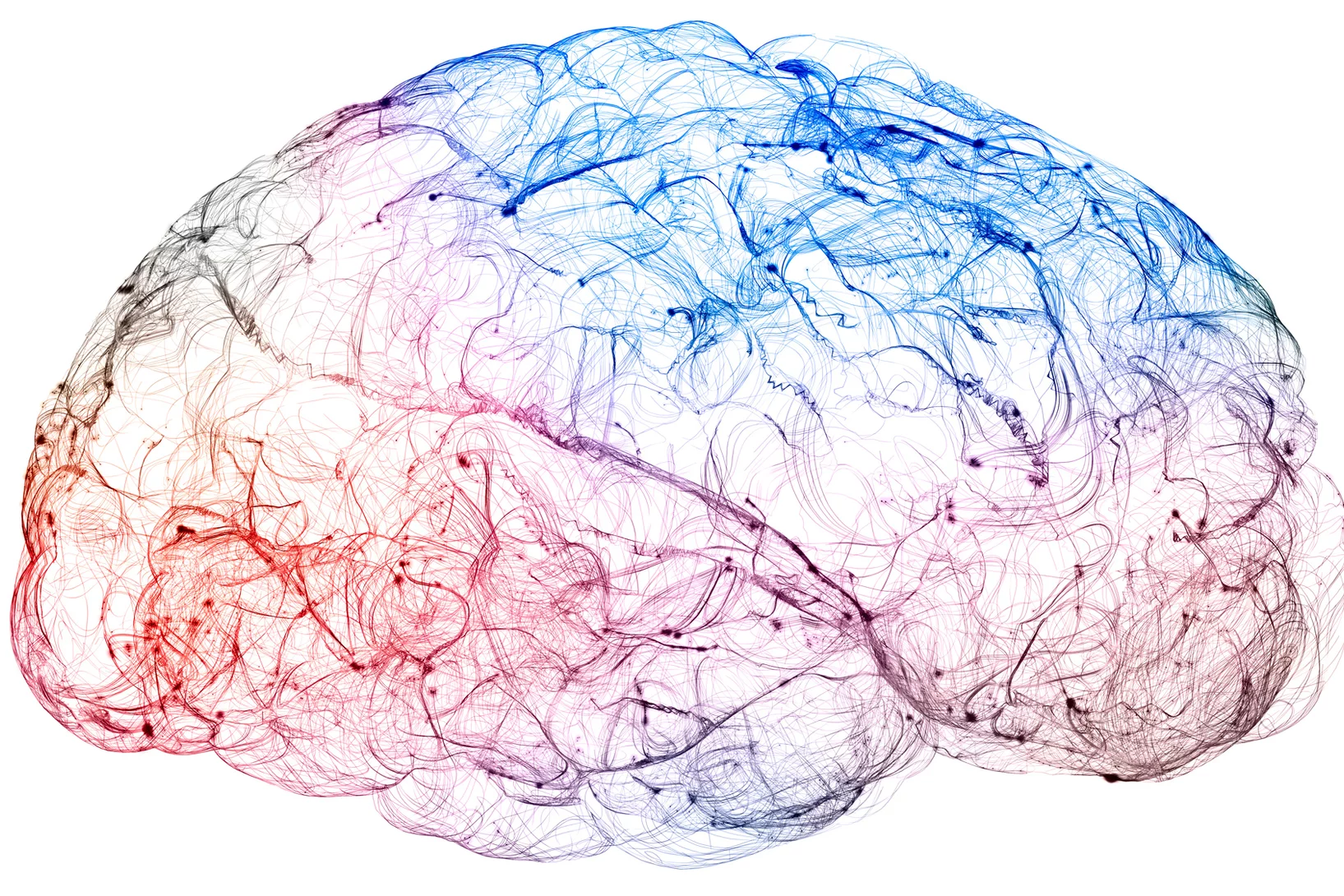

X-rays bring high-resolution brain mapping within reach

A new imaging breakthrough could reveal brain connectivity in 3D detail never before accessible.

Big heart, acute senses key to explosive radiation of early fishes

X-rays of a 400-million-year-old fossil illuminate a key moment in our deep evolutionary past.