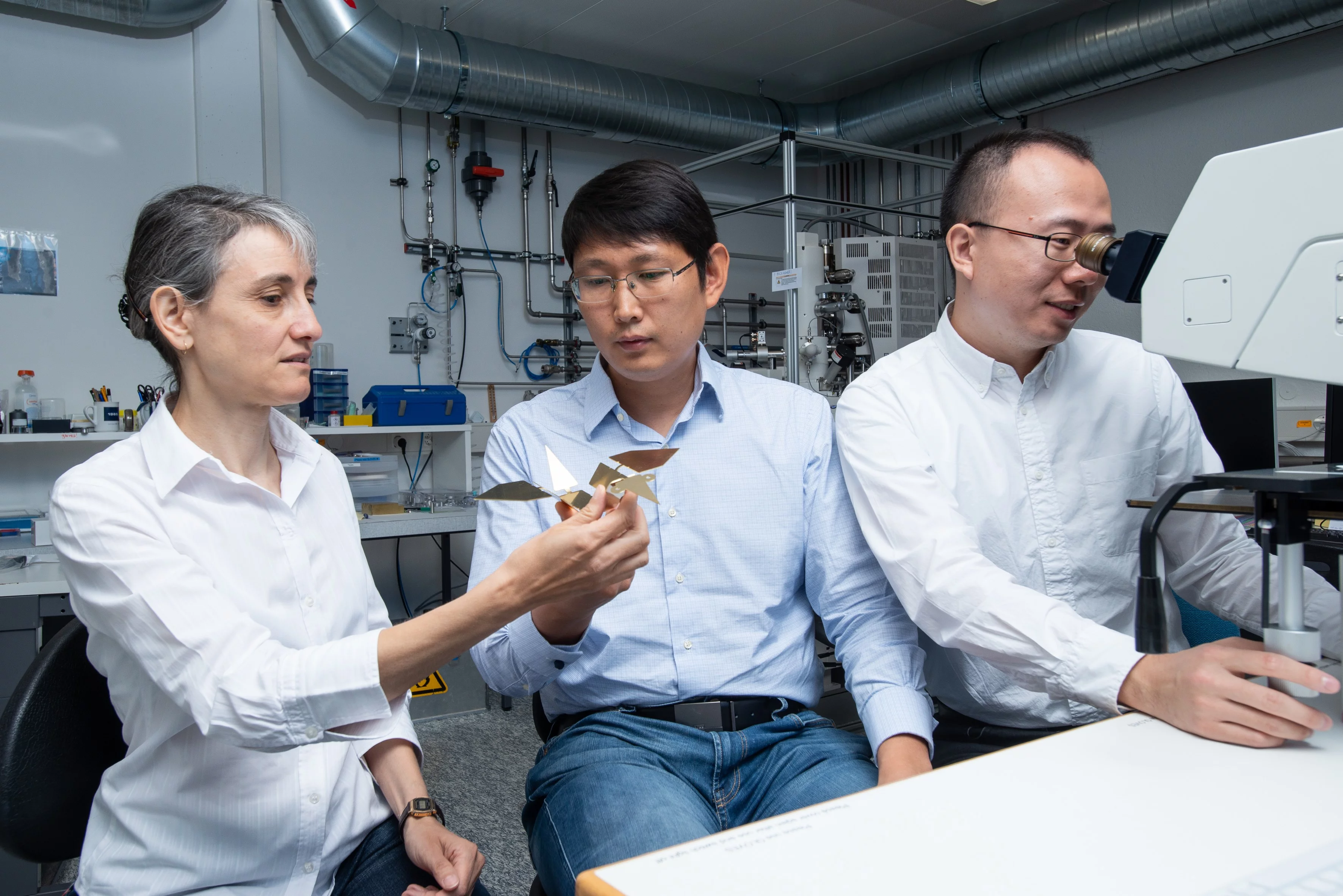

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and ETH Zurich have developed a micromachine that can perform different actions. First nanomagnets in the components of the microrobots are magnetically programmed and then the various movements are controlled by magnetic fields. Such machines, which are only a few tens of micrometres across, could be used, for example, in the human body to perform small operations. The researchers have now published their results in the scientific journal Nature.

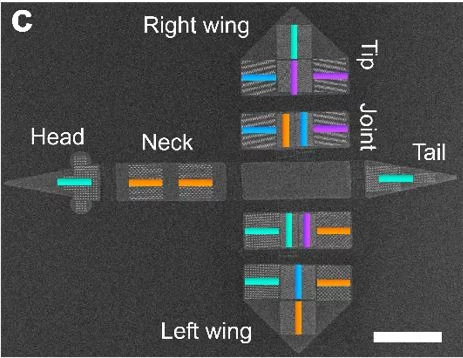

The robot, which measures only a few micrometres across, is reminiscent of a paper bird made with origami – the Japanese art of paper folding. But, unlike a paper structure, the robot moves as if by magic without a visible force. It flaps its wings or bends its neck and retracts its head. These actions are all made possible by magnetism.

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and ETH Zurich have assembled the micromachine from materials that contain small nanomagnets. These nanomagnets can be programmed to assume a particular magnetic orientation. When the programmed nanomagnets are then exposed to a magnetic field, specific forces act on them. If these magnets are located in flexible components, the forces acting on them cause the components to move.

Programming the nanomagnets

The nanomagnets can be programmed again and again. This reprogramming results in different forces, and new movements result.

For the construction of the microrobot, the researchers fabricated arrays of cobalt magnets on thin sheets of silicon nitride. The bird constructed from this material could then perform various movements, such as flapping, hovering, turning or side-slipping.

"The movements performed by the microrobot take place within milliseconds", says Laura Heyderman, head of the Laboratory for Multiscale Materials Experiments at PSI and professor for Mesoscopic Systems at the Department of Materials, ETH Zurich. "But programming of the nanomagnets only takes a few nanoseconds. This makes it possible to program the different movements one after the other. This means that the tiny microbird can first flap its wings, then slip to the side and afterwards flap again. "If needed, the bird could also hover in between", says Heyderman.

Intelligent microrobots

This novel concept is an important step towards micro- and nanorobots that not only store information to give a particular action, but also can be reprogrammed to carry out different tasks. "It is conceivable that, in the future, an autonomous micromachine will navigate through human blood vessels and perform biomedical tasks such as killing cancer cells", explains Bradley Nelson, head of Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering at ETH Zurich. “Other application areas are also conceivable, for example flexible microelectronics or microlenses that change their optical properties”, says Tianyun Huang, a researcher at the Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems at ETH Zurich.

In addition, applications are possible in which the characteristics of surfaces change. "For example, they could be used to create surfaces that can either be wetted by water or repel water", says Jizhai Cui, an engineer and researcher in the Mesoscopic Systems Lab.

The researchers have now published their results in the scientific journal Nature.

Contact

Original Publication

-

Cui J, Huang T-Y, Luo Z, Testa P, Gu H, Chen X-Z, et al.

Nanomagnetic encoding of shape-morphing micromachines

Nature. 2019; 575(7781): 164-168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1713-2

DORA PSI

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2300 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 450 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2025)