If Switzerland is serious about achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, a technological shift in personal vehicles is needed.

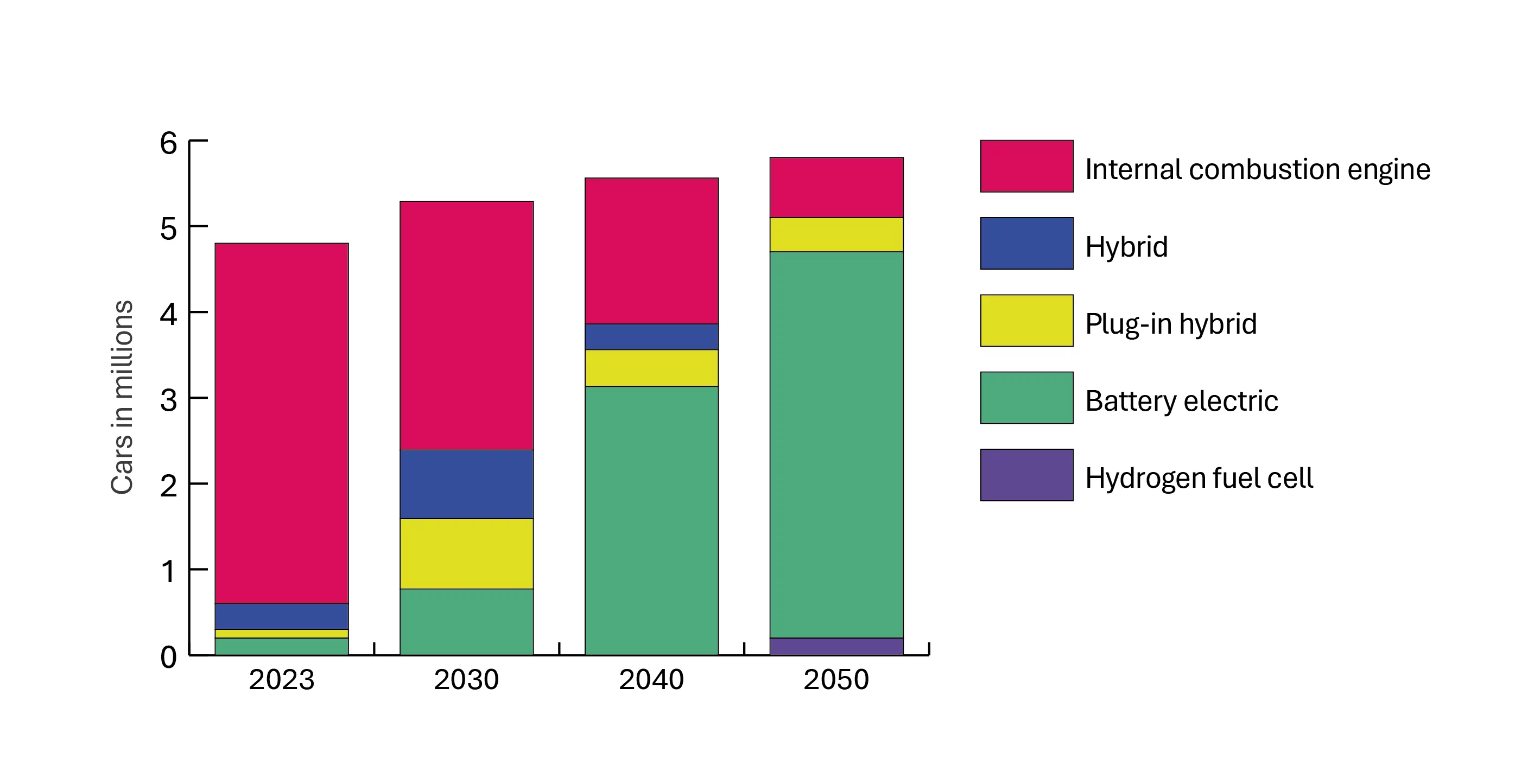

Most cars on the road today are internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) fuelled by diesel or gasoline. To achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, our research shows that the majority of cars will have to operate using an alternative power source. The alternatives to ICEVs fuelled by diesel or gasoline include battery electric vehicles (BEVs), hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, and ICEVs run on synthetic fuels.

In much of the world, including Switzerland, a transition to electric mobility has already begun. Governments are implementing policies specifically to encourage BEV adoption, including various financial benefits for owning “clean” or highly efficient vehicles. We will explore the reasons for why manufacturers and consumers might prefer BEVs to other powertrains in the column “What kind of juice?” In addition, from 2035, the EU is banning the sale of new petrol and diesel cars, unless they run on alternative fuels. However, many new car buyers are delaying making the switch, and this transition is not happening as swiftly as laid out in our net-zero scenario. Though BEVs are technologically ready for widespread adoption, there are several barriers to switching right now.

The first barrier is price. Today, expensive batteries drive up the purchase price of BEVs. However, despite requiring upfront investment, BEVs are cost-effective. In fact, over their entire lifetime, BEVs are competitive with internal combustion engine vehicles, taking into account expenses like insurance, service, tyres, fuel, and purchase cost. But most consumers looking to buy a vehicle do not take a life-cycle costing approach, meaning BEVs are still perceived as non-competitive without some form of subsidy.

A second barrier is misinformation about the low-carbon and sustainability credentials of BEVs in comparison with other types of private vehicles, including concerns about their batteries. Potential buyers might be discouraged from buying BEVs if they believe that the batteries end up as toxic waste. Recycling will play a crucial role in mitigating both problems. To provide an idea of the extent of these recycling programs, the EU aims for 73% of electric car batteries to be recycled by 2030. In addition, low-cobalt and entirely cobalt-free battery technologies are gaining momentum, helping to reduce demand for this rare, toxic, and often unethically sourced element.

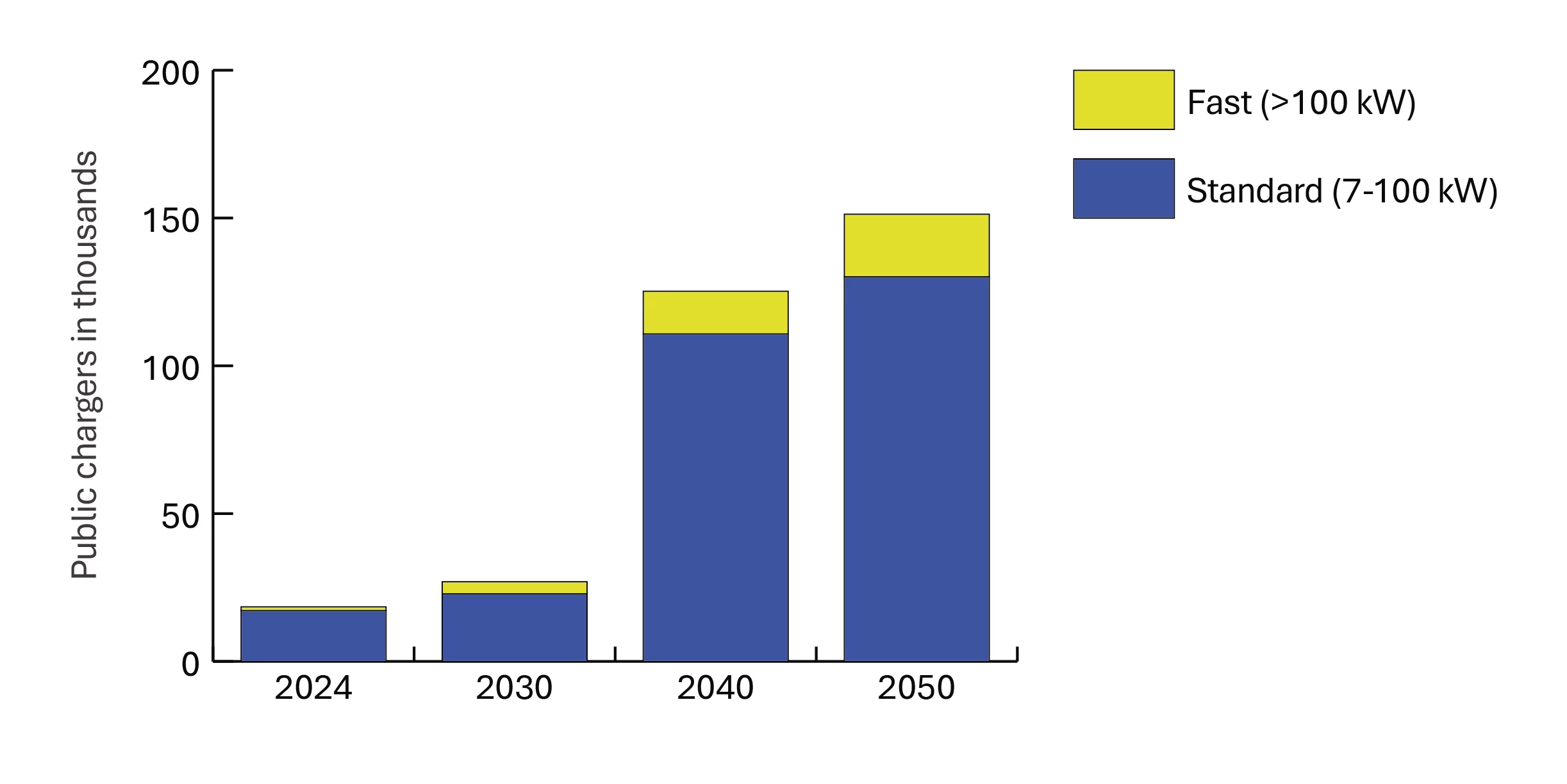

Another barrier to BEV adoption is concern about charging infrastructure availability. Overall, two out of three non-BEV owners cite access to charging infrastructure as the main barrier to purchasing a BEV.

Home charging is a big part of this. Among BEV early adopters, the majority installed a private charging station. Today, with the improving access to public chargers, the proportion of Swiss BEV owners with private chargers has dropped to just one in three. Home charging with a private charger is convenient, time efficient, and inexpensive, given that the residential electricity tariffs come without the public chargers’ fees. Our research shows that providing overnight charging access through private home chargers or public chargers in residential areas helps increase BEV penetration by 12–20% during the period between 2040 and 2050.

In addition to home charging, charging on the go and during the day is also important. Among drivers without private home charging, a 24% higher BEV uptake is observed when public infrastructure in non-residential areas is significantly improved, rather than when it is not. This includes chargers in public parking garages, store parking lots, and highway charging stations, for example.

The figure above shows how the number of charging stations in Switzerland needs to increase substantially to support BEV uptake. According to our analysis, each BEV needs about 5 kW total charging capacity, split into around 2 BEVs per private charger and between 25 and 30 BEVs per public charger. This means that, by 2050, Switzerland will need more than eight times as many regular public chargers and sixteen times as many fast public chargers as today.

BEV charging infrastructure needs to be extended on multiple fronts. The installation of home chargers remains an issue, especially since most people in Switzerland rent their homes, and tenants in Switzerland do not have the right to install BEV chargers in their buildings. Public chargers in residential areas can mitigate this issue. A combination of public chargers to use on the go, in commercial areas, and at workplaces can also help fill the gap.

Inadequate charging infrastructure for BEVs today could lead to costly inefficiencies down the road. These findings underscore how important charging infrastructure is to maintain the BEV trends.