Future Technologies

The manifold characteristics of materials are determined by what type of atoms they are made of, how these atoms are arranged, and how they move. In the research area Future Technologies, scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute are trying to clarify this link between the internal structure and the observable properties of different materials. They want to use this knowledge as fundamental principles for new applications – whether in medicine, information technology or energy generation and storage – or to explore innovative manufacturing processes for industry.

Find out more at: Future Technologies

Astral matter from the Paul Scherrer Institute

Processes in stars recreated with isotopes from PSIIsotopes that otherwise only naturally exist in exploding stars à supernovae à are formed at the Paul Scherrer Institute’s research facilities. This enables processes that take place inside the stars to be recreated in the lab. For instance, an international team of researchers used the titanium isotope Ti-44 to study one such process at CERN in Geneva. In doing so, it became evident that it is less effective than was previously believed and the previous theoretical calculations of processes in stars need to be corrected.

Observed live with x-ray laser: electricity controls magnetism

Researchers from ETH Zurich and the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI demonstrate how the magnetic structure can be altered quickly in novel materials. The effect could be used in efficient hard drives of the future.

Superconductivity switched on by magnetic field

Superconductivity and magnetic fields are normally seen as rivals à very strong magnetic fields normally destroy the superconducting state. Physicists at the Paul Scherrer Institute have now demonstrated that a novel superconducting state is only created in the material CeCoIn5 when there are strong external magnetic fields. This state can then be manipulated by modifying the field direction. The material is already superconducting in weaker fields, too. In strong fields, however, an additional second superconducting state is created which means that there are two different superconducting states at the same time in the same material.

Electrons with a "split personality"

Above the transition temperature, some electrons in the superconducting material La1.77Sr0.23CuO4 behave as if they were in a conventional metal, others as in an unconventional one à depending on the direction of their motion. This is the result of experiments performed at the SLS. The discovery of this anisotropy makes an important contribution towards understanding high-temperature superconductors. The effect will also have to be taken into account in future experiments and theories of high-temperature superconductors.

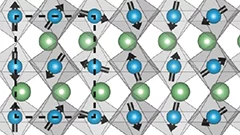

Towards sodium ion batteries – understanding sodium dynamics on a microscopic level

Understanding sodium dynamics on a microscopic levelLithium ion batteries are highly efficient, But there are drawbacks to the use of lithium: it is expensive and its extraction rather harmful to the environment. One possible alternative might be to substitute lithium with sodium. To be able to develop sodium-based batteries, it is crucial to understand how sodium ions move in the relevant materials. Now, for the first time, scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have determined the paths along which sodium ions move in a prospective battery material. With these results, one can now start to think of new and specific ways to manipulate the materials through slight changes to their structure or composition, for example à and thereby achieve the optimized material properties necessary for use in future batteries.

Neutrons and synchrotron light help unlock Bronze Age techniques

Experiments conducted at the PSI have made it possible to determine how a unique Bronze Age axe was made. This was thanks to the process of neutron imaging, which can be used to generate an accurate three-dimensional image of an object’s interior. For the last decade, the PSI has been collaborating with various museums and archaeological institutions both in Switzerland and abroad. The fact that the 18th International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, which is to be held at the University of Zurich from 3 à 7 September, will also be meeting at the PSI for one day is a testament to the success of the cooperation.

Magnetisation controlled at picosecond intervals

A terahertz laser developed at the Paul Scherrer Institute makes it possible to control a material’s magnetisation precisely at a timescale of picoseconds. In their experiment, the researchers shone extremely short light pulses from the laser onto a magnetic material. The light pulse’s magnetic field was able to deflect the magnetic moments from their idle state in such a way that they exactly followed the change of the laser’s magnetic field with only a minor delay. The terahertz laser used in the experiment is one of the strongest of its kind in the world.

Ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic – at the same time

Researchers from the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) have made thin, crystalline layers of the material LuMnO3 that are both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic at the same time. The LuMnO3 layer is ferromagnetic close to the interface with the carrier crystal. As the distance increases, however, it assumes the material’s normal antiferromagnetic order while the ferromagnetism steadily becomes weaker. The possibility of producing two different magnetic orders within a material could be of major technical importance.

The cleanest place at the Paul Scherrer Institute

Highly sensitive processes take place in the cleanrooms of the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) as a single dust particle in the wrong place could have disastrous consequences. Here is a glimpse behind the scenes in rooms that are so clean even pencils are prohibited.

Experiments in millionths of a second

Muons à unstable elementary particles à provide scientists with important insights into the structure of matter. They provide information about processes in modern materials, about the properties of elementary particles and the nature of our physical world. Many muon experiments are only possible at the Paul Scherrer Institute because of the unique intense muon beams available here.

Tiny Magnets as a Model System

Scientists use nano-rods to investigate how matter assemblesTo make the magnetic interactions between the atoms visible, scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have developed a special model system. It is so big that it can be easily observed under an X-ray microscope, and mimics the tiniest movements in Nature. The model: rings made from six nanoscale magnetic rods, whose north and south poles attract each other. At room temperature, the magnetisation direction of each of these tiny rods varies spontaneously. Scientists were able to observe the magnetic interactions between these active rods in real time. These research results were published on May 5 in the journal Nature Physics.

Germanium – zum Leuchten gezogen

Forscher des PSI und der ETH Zürich haben mit Kollegen vom Politecnico di Milano in der aktuellen Ausgabe der wissenschaftlichen Fachzeitschrift "Nature Photonics" eine Methode erarbeitet, einen Laser zu entwickeln, der schon bald in den neuesten Computern eingesetzt werden könnte. Damit könnte die Geschwindigkeit, mit der einzelne Prozessorkerne im Chip miteinander kommunizieren, drastisch erhöht werden. So würde die Leistung der Rechner weiter steigen.This news release is only available in German.

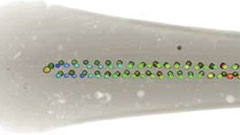

X-ray Laser: A novel tool for structural studies of nano-particles

Prominent among the planned applications of X-ray free electron laser facilities, such as the future SwissFEL at the Paul Scherrer Institute, PSI, are structural studies of complex nano-particles, down to the scale of individual bio-molecules. A major challenge for such investigations is the mathematical reconstruction of the particle form from the measured scattering data. Researchers at PSI have now demonstrated an optimized mathematical procedure for treating such data, which yields a dramatically improved single-particle structural resolution. The procedure was successfully tested at the Swiss Light Source synchrotron at PSI.

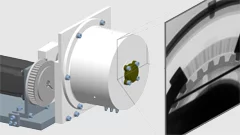

Observing Engine Oil Beneath Metal

Developmental Engineers from the firm LuK (D) wanted to see right through the metal housing of a clutch. They wanted to observe how the oil that lubricates and cools a clutch is distributed. A transparent disc becomes dirty very quickly, and X-rays merely reveal the metal. These engineers therefore turned to scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute, who illuminated the metal with neutrons and thus made the lubricating oil visible. The results surprised everyone: only three of the eight lamellae were sufficiently lubricated.

Superconductors surprise with intriguing properties

Scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute, together with Chinese and German collaborators, have obtained new insights into a class of high-temperature superconductors. The experimental results of this fundamental research study indicate that magnetic interactions are of central importance in the phenomenon of high-temperature superconductivity. This knowledge could help to develop superconductors with enhanced technical properties in the future.

Imaging fluctuations with X-ray microscopy

X-rays are used to investigate nanoscale structures of objects as varied as single cells or magnetic storage media. Yet, high-resolution images impose extreme constraints on both the X ray microscope and the samples under investigation. Researchers at the Technische Universität München the PSI now showed how to relax these conditions without loss of image quality. They further showed how to image objects featuring fast fluctuations, such as the rapid switching events that determine the life time of data storage in magnetic materials.

Magnetic nano-chessboard puts itself together

Researchers from the Paul Scherrer Institute and the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research have been able to intentionally switch off’ the magnetization of every second molecule in an array of magnetized molecules and thereby create a magnetic nano-chessboard’. To achieve this, they manipulated the quantum state of a part of the molecules in a specific way.

Excitement that rivals a moon landing

Interview with Thomas HuthwelkerThe Paul Scherrer Institut makes its research facilities available to scientists from all over the world. To ensure these scientists are exposed to optimal conditions when they arrive is the hard work of many PSI staff. An interview with one of these scientists provides a glimpse behind the scenes. This interview is taken from the latest issue of the PSI Magazine Fenster zur Forschung

Silicon – Close to the Breaking Point

Stretching a layer of silicon can lead to internal mechanical strain which can considerably improve the electronic properties of the material. Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute and the ETH Zurich have created a new process from a layer of silicon to fabricate extremely highly strained nanowires in a silicon substrate. The researchers report the highest-ever mechanical stress obtained in a material that can serve as the basis for electronic components. The long term goal aim is to produce high-performance and low-power transistors for microprocessors based on such wires.

Built-in Germanium Lasers could make Computer Chips faster

Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) researchers have investigated the mechanisms necessary for enabling the semiconductor Germanium to emit laser light. As a laser material, Germanium together with Silicon could form the basis for innovative computer chips in which information would be transferred partially in the form of light. This technology would revolutionise data streaming within chips and give a boost to the performance of electronics.